In this essay I don’t provide context for my assertions. That is provided in my essays on Peterson and Rother.

Spirituality is an intuitive substitute for the ambition to improve the world tangibly. It’s like depression. It keeps us from getting killed by going back and challenging the alpha too soon. We know, somehow, that we have to aim very high, to be roused, and to provide context to our mundane efforts. Mediocrity isn’t motivating.

The patterns that Peterson illustrates in Maps of Meaning are essentially the same, minus important details, as Rother’s Improvement Kata illustration. Peterson’s illustrate the structure of our most enduring religious myths. They are abstract and spiritual. Rother’s is the meta-pattern that guides the lower-level patterns. It is pragmatic, a training tool, a pragmatic ritual. It is an infinitely scalable pattern. It rouses and provides context.

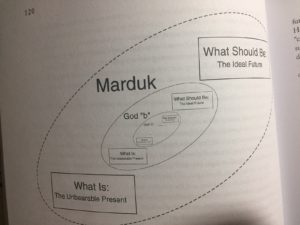

From Maps of Meaning, one of many illustrations of the ascent from the unbearable present towards an ideal vision of the future, iteratively.

From Maps of Meaning, one of many illustrations of the ascent from the unbearable present towards an ideal vision of the future, iteratively.

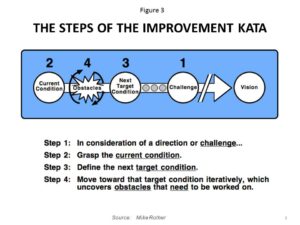

Rother’s Improvement Kata, his model that makes explicit what he inferred to be happening organically at Toyota.

Rother’s Improvement Kata, his model that makes explicit what he inferred to be happening organically at Toyota.

These models are vital. We need them.

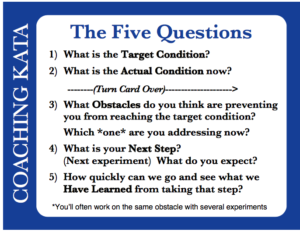

I’ve been working this pattern with five Learners for two weeks. Each session, I ask them the coaching questions.

Spirituality aligns one’s actions with a transcendent objective. Heaven and hell are intuitive concepts. Yuval Noah Harari observes that spirituality is trailblazing. It is the elements of religion without the rules, without the precedent. It’s exploratory.

Harari defines religion this way:

Religion is anything that confers superhuman legitimacy on human social structures. It legitimises human norms and values by arguing that they reflect superhuman laws.

In spirituality, you are working without the norms, in some way. Obviously, you are operating inside some set of norms, insofar as you must or are inclined to.

Persisting in spirituality (exploring) without striving to orient to both a zenith and a nadir primes the mind for hedonism and ennui or worse. Attaining a goal for which you have strived is depressing unless that goal is only a milestone.

If survival isn’t a challenge, then we can be hedonistic. If we’ve learned better than that, we can be spiritual or religious. If we’re disillusioned, we can revert back to some variety of hedonism. If we continue beyond our disillusionment, we can set unattainable mundane direction, and challenges that force us to change our minds.

The intuitive understanding is important and has to come first. Steps don’t get skipped only delayed. But to stop at the step of spirituality without developing a vision and a plan to move towards the ideal in this life is a to misunderstand the path. We encourage each step along the path so that we can continue making steps.

So it’s tricky. We have to be empirical and objective and follow nature on our path. Our path must be terrestrial. But it must lead to heaven, which also must be terrestrial. And if we cause violence, we’ve set our fate. We’ve ruined everything.

Complacency is deceptive. It seems bad but is much worse. No one is harmless. This is the basis for Maps of Meaning. Peterson is known for talking about how to live a meaningful life, but his impetus for his research was to understand why people commit atrocities. You can’t understand one without understanding the other.

Stoic philosophy emphasizes virtue ethics. Virtue ethics is pragmatic because one’s virtue is one’s destiny. When we talk about virtue, we are talking about the characteristics of the agent. We’re talking about habits and habit formation—myelination of the axon.

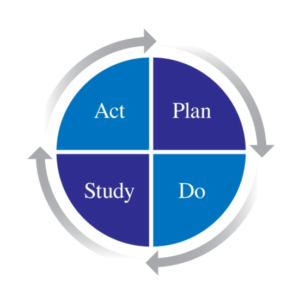

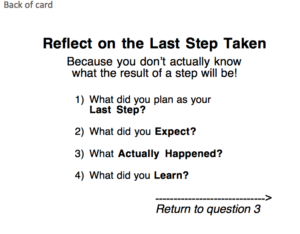

So while a Stoic would advocate focusing on what you can control and detaching yourself from the outcome, in Rother’s method, the application of the scientific method to daily activities, we use the Deming Cycle:

- plan and make a prediction, focusing on what you can control,

- execute your plan faithfully (do),

- study the results,

- reflect on the meaning of those results and attempt to draw conclusions, or rather, material for a revised theory and a new prediction, on which you act, and

- formulate a new plan again.

It’s not the essayification of everything. It’s continual experimentation. It isn’t revelatory, either. Or reading about it isn’t. You already know about it. It’s been embedded in our culture for thousands of years.

If we understand Buddhism, Stoicism, and Pragmatism in our bones, then we’ll understand that religion and spirituality are stepping stones. Not bad, just inferior.

The Ionian philosophers were using pure reason, were essayifying everything. The next step is to develop an experiment. Document everything. And experiment again.

But what happened with Buddhism is happening with science. The call to study what is in order to learn what can be is giving way to dogmatism. Research is being preached instead of questioned and demonstrated.

A trap that I see my peers fall in is to treat published papers like scripture, to overestimate the value of others’ research as it pertains to them. There is no substitute for direct experimentation. And our experimentation should emulate the quality of those that pass peer review, but, failing that, we shouldn’t fail to experiment. Instead, the poorer the quality of the experiment, the more modest our conclusion should be. Which is fine. Even a very good experiment on only yourself may only tell you about yourself. That’s an admirable start.

If we design the experiment to our utmost, then our job is to identify the limitations of what conclusions we can draw from it. Then perform another experiment.

Worshipping published research is maybe better than worshipping an idol, but maybe worse than worshipping an imaginary character who lives in and knows your heart and always gives you heaven-sent advice. The imagined personal savior is at least abstract and amorphous. It can grow with you. The meaning of research can only grow and expand with additional research. We can’t shirk our own flawed experiments.

The method for detaching yourself from the outcome is to treat all efforts to achieve an aim as an experiment. Every time you do an experiment, make a prediction (a description and a metric), execute faithfully, and gather the results. Study the results. Day dream. What did you learn. Be parsimonious. What did you learn? Be ruthless. What did you learn? Are you sure?

Use those results in the planning and prediction phase of your next experiment.

Imagine if prayer were replaced with meditation, and meditation on the breath were supplemented with meditation on the results of the last experiment and what the next experiment should be. Instead of attachment to outcomes, holding fast to this iterative process.

A Buddhist would have you detach yourself from all outcomes, actually stop outcomes. That’s the goal.

Outsourcing our experiments to others is unethical, because it deprives our soul of direct experience.

“As long as our brain is a mystery, the universe, the reflection of the structure of the brain, will also be a mystery.”

The basis of objective scientific method is inherently flawed. So, relying more and more on dogma to maintain it’s not so super-human legitimacy makes sense. Our experience is subjective. There is no outside of the universe or nature, we are nature, so a laboratory will never cut it. I agree we must experiment through our subjective experience and find the subjective-objective. The reality of ourselves. Who we are. Where we are going. Then plan. Do. Study the results. Awesome blog mate!

Thanks. Everything is flawed, so you need both, right?