A friend of mine has started writing vignettes. He told me about them in a recent conversation. I asked to read one, and he agreed. We met at a park between his apartment and mine, beneath a tree, though it was cloudy. He had decided to print it on 5 ½” x 8 ½” sheets of paper, with ½” margins, in Calibri typeface. He had elected to laminate them, so that the effect, as I read beneath a sweet gum tree, was of flipping through a stack of photographs, or rather of oversized photographic plates.

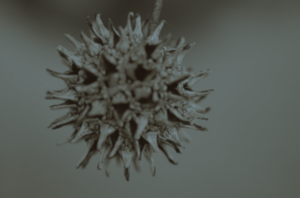

It was particularly windy, and, in one of the gusts, a torrent of spiky sweet gum seeds fell around me, a few striking me. Rain clouds gathered, and the air developed a verdant glow.

I was dismayed. With curious efficiency he had made characters and scenes so evocative that I suspected part of the effect had been caused by his curious printing choices. In my own writing, the characters were burdened with autobiographical detail.

After I had finished reading the plates of text, I handed them back to him and asked why he had started writing vignettes in this way. He explained that two months prior he had had a dream in which a paler copy of himself was floating a short distance in front of him, the whites of its eyes minutely rippling as if submerged in a shallow pool. He had felt in this dream a hollowness in the air in front of him, which gave walking a curious buoyancy, yet also a slowness. In this way he chased the figure, which eventually floated away, its one hand pocketed, its eyes wide, its blonde hair tossing mutely in the thin atmosphere, its other hand reaching for him.

Waking up the following morning, he had perfect recollection, not only of the images in the dream, but of the feeling of it, which was unlike any he had experienced before. He explained that he wanted to know whether anyone else had also felt that way, so he tried to write something that would evoke the feeling in the reader, so he could ask them whether it was familiar to them or strange.

I thanked him for the opportunity to read his vignette and told him I had to be getting back. As I covered the few blocks to my apartment, I interrogated myself concerning my own writing decisions. Why did I burden the characters in my stories with my own personality?

Three answers came readily to mind.

The first was that, since I had only ever experienced emotions as myself, I had inferred that I could not describe an emotion with fidelity without putting it in the context of my personality.

Second, watching movies and television throughout my life, I had found it uncomfortable how the characters were so straight forward, as if each were a token for a class of personality. Being prone to self-loathing, I found myself alternately envying one archetype one week and an apparently incompatible one the next. This made their incompatible experiences inaccessible, as if each person had their own pure, vital essence, whereas mine was mercurial and exhausting.

Or, worse, a story that prides itself on defying expectations—a motivational speaker who spends his nights carefully planning suicide, or a behemoth that loves cuddles. Ah yes. People aren’t what they at first seem. I felt that this trick, so ubiquitous and stupid, was somehow evidence that stories produced few fruits. The scarcity made me fearful and, like the slave with but one talent, I chose to hold onto what I had, deploying tiny and simplistic versions of myself onto the page, hoping that they might at least be evocative in tiny and simple ways.

Third, it seemed that I had somewhere along the way allowed the motivation to evoke in the reader a certain feeling to be outweighed by the motivation to make the reader understand what it felt like to be me, or at least to have lived through particular experiences I had found impactful.

But here my friend had been so much cleverer. He created strikingly muted characters, characters that hardly existed, and in the way that they did exist, it was primarily through setting and their interactions with one another. In this way the feeling of the story was held out close to the reader.

As I entered the building, my mind wandered to scenes in Charlie Kaufman movies and to some remarks that Kazuo Ishiguro had made about Marcel Proust. It struck me that both of these artists (Kaufman and Proust) had made decisions like my own—they had felt that they had to rely on biographical accuracy in order to achieve emotional accuracy—while Ishiguro had made a decision like the one my friend had made.

In particular I found myself contrasting The Unconsoled with Synecdoche, New York. Both are in a way exhaustive. Both appear to be works of a completist. Yet while The Unconsoled efficiently cycles through frame after frame of experience, sharing a lifetime with the reader through ingenious metaphorical devices, Synecdoche, New York seems to do something less. It depicts the construction of an awful, gargantuan movie set by a director who believes that adding details somehow adds life. Yes, the movie mocks this idea, but it also exaggerates and amplifies it, minimizing its own availability to evoke more than a few contrived and complicated emotions, which, because of their specificity, seem specific to its characters.

Arriving back at my apartment, I felt queasy, and I had to lie down. My phone vibrated. It was my friend. He had forgotten to ask me: had it—had reading the story—felt that I was looking back over periods of my life? Had it felt like distilled recollections of what it had been like to live through what at the time hadn’t felt like any notable kind of experience but in retrospect did feel like a kind of experience? Had it felt like vistas?

I told him it had.